How to talk to your child about internet safety – and not become a toxic parent

The Internet to a child is like a huge yard with no fences. There are friends, games, and dangerous strangers. You want to “put up a fence,” but the more control you have, the less trust you have. The parent’s job is not to forbid, but to teach.

Internet is not a threat, but a part of life

The alpha generation has grown up online. According to Mediascope, 96% of 12-17 year olds use the internet daily. The smartphone is the main gadget, and social networks, messengers and video platforms are a familiar medium for communication and study.

Smartphones are the main gadget, and social networks, messengers and video platforms are a familiar medium for communication and study.

But that’s where the risks lie: fake accounts, viral Challenges, chat room scammers. The idea that “it’s easier to ban the internet” hasn’t worked for a long time. Even if a teenager wanted to, it would be impossible for him or her to give up online completely: too much of his or her life takes place online. The task of the parent is not to restrict access, but to understand what is happening in the digital environment and to be able to talk about it with the child so that he or she does not shut down.

Start with what interests the child

Modern kids absorb advice better in familiar formats – videos, podcasts, games. For example, the Sound service has a podcast “Kids for Kids”, where the series “Cybersecurity” is built like a mini-detective. The heroes – children themselves – discuss what to do if a stranger writes to you, you receive a suspicious message, or you get caught by a “fraud bot”. Listening to the episode together is a great way to start a conversation: “What would you do in that situation?”

Ano Digital Economy in its project “Lesson of Digital” teaches how to create strong passwords and recognize phishing, talks about cybersecurity of the future with Kaspersky, and how to observe “digital hygiene” when communicating with AI-assistants with Yandex. And there’s information for both children and adults, with lessons to suit different age groups.

And the “I-risk” service from Doctors to Children simulates real online situations, for example, you have to choose from several posts on a social network which one is safe and which one is not. This practice allows to understand in a non-boring game form, using real examples, how to filter content online.

These approaches don’t look boring – it’s about finding answers together with your child and making it fun for them, which means they learn better.

Talk, not lecture

The main thing that gets in the way of parenting is intonation. Start with “I’m going to explain to you how to do it right,” and the dialog turns into a lecture that the child stops listening in the second minute. For the conversation to work, it should be like an exchange of experience, not an instruction. A good way is to start not with a warning, but with interest. Instead of “don’t trust strangers on the Internet,” it’s better to ask, “Have you ever been emailed by someone you didn’t know? How did you realize he wasn’t real?” Such a question doesn’t sound controlling; it opens the door to sharing experiences. Even if the teenager brushes it off, he or she will still feel like it’s okay to talk to you about it.

Personal example works, too. A parent who says, “I recently got a letter from the bank, and I almost didn’t believe it was real,” shows that it’s not just kids who have trouble on the Internet. It’s a move that removes distance and gives teens the right to make their own mistakes.

An important point is emotion. If a child tells you that someone tricked or frightened him or her, the reaction “Why did you go there?” closes the subject for good. It’s much more effective to say, “It’s good that you told me. Let’s think together about what we could have done differently.” Then even an unpleasant experience becomes a reason to talk and learn, not a source of shame.

Agree, not forbid

One of the biggest mistakes parents make is to set rules “from above”: “turn off the phone at nine o’clock,” “don’t add new friends online,” “don’t download anything without asking. Such attitudes cause protest and a desire to circumvent the prohibition. Teenagers are usually more successful at this than adults: they create backup accounts, use messengers that their parents don’t know about, or simply erase traces of correspondence.

Much more effective is a digital contract. Ask:

- “How much time online seems normal to you?”

- “What do we do if a stranger texts you?”

A teenager feels that his or her opinion is being taken into account and becomes involved in making decisions.

It’s important that the rules apply not just to the child, but to the whole family. If a parent forbids social media, but endlessly scrolls through the feeds, there will be no trust. Shared agreements work better: for example, “phones are kept aside at dinner” or “we don’t discuss each other’s private messages without permission”. This shows that digital hygiene is not a punishment, but a common norm.

Solve it yourself

Before you talk to your child about safety, it’s important to understand exactly what you want to protect them from.

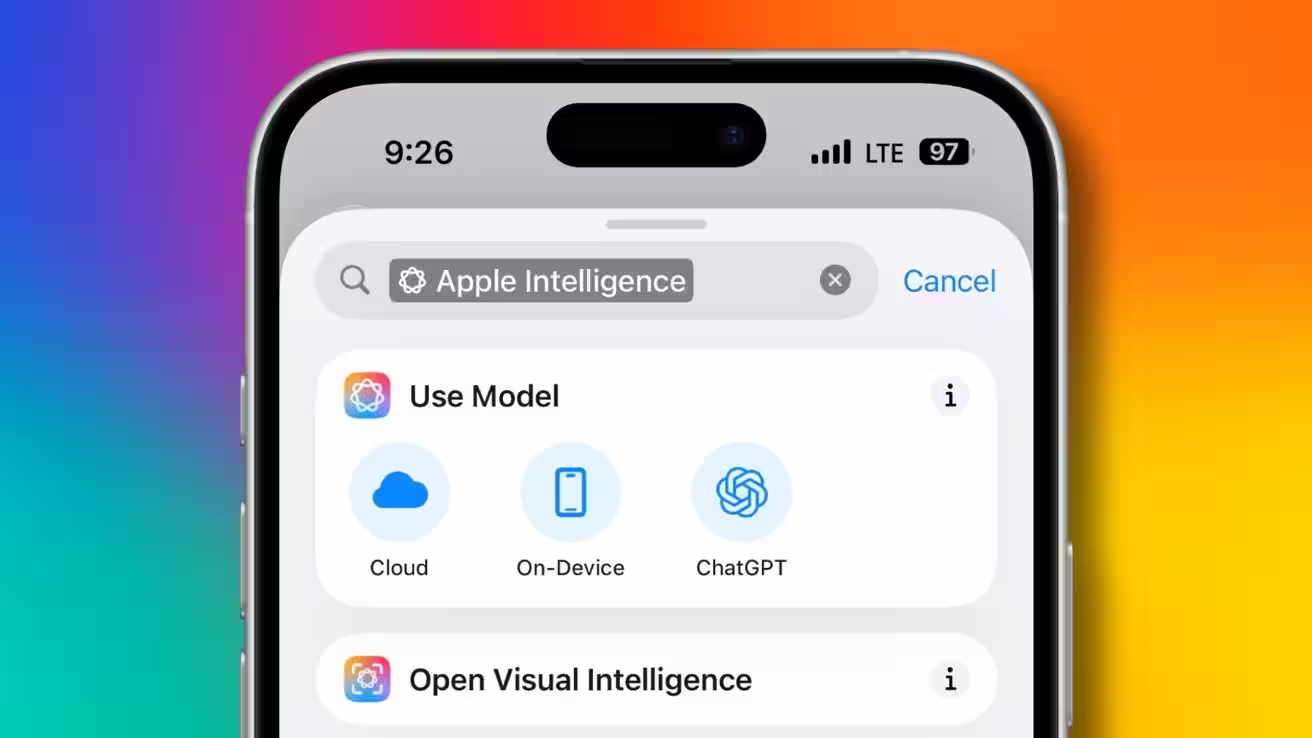

Today’s threats are more subtle. A child can receive a chat message from a “classmate” asking for money “to play a game,” or see a TikTok challenge video that masquerades as fun but actually encourages dangerous behavior. Or meet a person in Discord who appears to be a peer, but gradually builds trusting communication with the purpose of manipulation. Classic link phishing has not gone away either. Today, new technologies are emerging: deepfake videos, fake voice messages, and photos created by neural networks. They look more and more convincing, and even adults without critical thinking skills are finding it difficult to recognize them.

So the first step is to broaden your own horizons. See what apps your child actually uses and try to understand them, at least superficially: what features they have, what users are complaining about, what scams are in the news. This isn’t about becoming a cybersecurity expert, it’s about stopping talking to your child blindly.

Trust is the best antivirus

Mistakes and deceptions are part of digital life. It’s important for a child to know that they can tell – and not be judged. Control and punishment breed secrecy. And calm conversation breeds trust. The Internet won’t become safe on command, but with an attentive adult, it’s no longer a territory of fear.